The Pine That Built a Nation and the Tiny Worm that Could Sneak In

In New Zealand, Pinus radiata is much more than just another tree. It is the backbone of the country’s commercial forestry, stretching across almost 1.57 million hectares and making up more than 90% of all planted production forests. It supplies nearly all of our domestic timber and around four million cubic metres of export logs each year.

From Kiwi Forests to China and Korea

Radiata pine dominates our forestry exports. In the year to June 2024, the sector earned $5.75 billion. China received 57% of that total, with South Korea the second largest destination. In just the first three months of 2024, approximately 5.48 million cubic metres of logs were shipped to China and 268,000 cubic metres to South Korea, the great majority of it radiata pine.

From Forest Mystery to Scientific Discovery

In March 2019, something unusual was happening in Kaingaroa Forest in the central North Island. During a routine forest health survey, inspectors found radiata pines dying quietly and without any obvious cause.

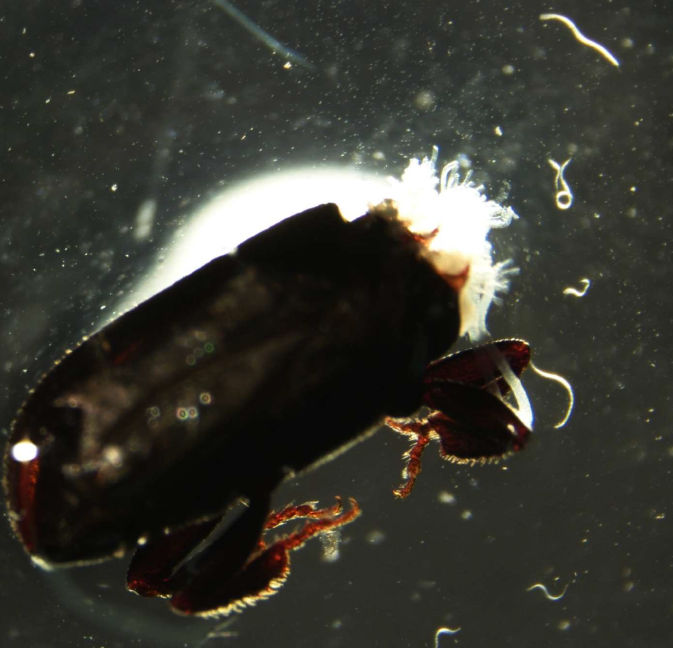

One dead tree was examined on the spot. The trunk was soaking wet as if it had been standing in water, but there were no signs of fungal disease or insect attack. To investigate further, the team felled three nearby trees and another that was already dead. Cutting into the trunks revealed dark patches of “sapstain” and waterlogged wood that dripped when cut. Beetles hiding inside the trees were also collected. All of these samples were sent for tests to check for nematodes, tiny worms that can live in wood.

The results were surprising. Nematodes were found in the wood and in a bark beetle called Hylastes ater. A Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research scientist, working with the Ministry for Primary Industries’ Plant Health and Environment Laboratory, examined the nematodes closely. Under the microscope they looked just like a species first described in Europe, Bursaphelenchus hildegardae.

DNA testing confirmed the match, showing up to 100% similarity with specimens from Germany. This was the first time B. hildegardae had been found in New Zealand’s forests. What began as a routine check had turned into the discovery of a new chapter in the country’s biosecurity story.

The Power of a Collection

The investigation made use of a national scientific treasure, the New Zealand Arthropod Collection (NZAC) – Ko te Aitanga Pepeke o Aotearoa at Landcare Research. This is an enormous archive of insects from across the country, preserved with great care over decades.

Researchers reviewed past records of Bursaphelenchus nematodes in New Zealand and located the original specimens from earlier studies so they could be re‑examined with modern methods. They studied dried Hylastes ater beetles from Scion and also looked at beetles preserved in alcohol, including H. ater and another possible carrier, Hylurgus ligniperda. These specimens came from a wide range of institutions, including the New Zealand Arthropod Collection, Auckland Museum, Te Papa, Lincoln University’s Entomology Research Museum, Canterbury Museum, Scion, Massey University and MPI’s Plant Health and Environment Laboratory.

No B. hildegardae were found in any of the older specimens. Even so, the process proved the immense value of such collections. They allow researchers to look back in time and see what lived in our forests decades ago. If the nematode had been present in those historical samples, it would have shown that B. hildegardae had been in New Zealand for many years without causing harm. In that case, the emergency closure of Kaingaroa Timberlands Forest in 2019 might never have happened. Collections make it possible to understand the past and use that knowledge to make better decisions about whether a newly found organism is a serious threat or an old resident that has simply gone unnoticed.

The Global Menace of Pine Wilt Nematode

Among pine‑killing nematodes, B. xylophilus, also known as the pine wilt nematode, is the most feared. Originating in North America, it has spread to Asia and Europe, killing huge numbers of susceptible pines. In Japan it destroys millions of trees every year and has been a major forestry problem for over a century. In Portugal and Spain it has triggered costly eradication and containment programmes, with the European Union spending hundreds of millions of euros to slow its spread.

The damage is not only ecological but also economic. Timber production collapses, biodiversity declines and once‑green coastal forests become expanses of grey, lifeless trunks. In South Korea, B. xylophilus, nicknamed the “pine AIDS” nematode, has been devastating forests since 1988. It spreads through Japanese pine sawyer and Sakhalin pine sawyer beetles, killing vast areas of native pines and forcing expensive replanting efforts that continue today.

Why Monoculture is a Risk Multiplier

Radiata pine forests in New Zealand form one vast monoculture. Millions of genetically similar trees stand in uniform rows. This makes planting and harvesting efficient, but it leaves the industry highly vulnerable to pests and diseases. In a mixed forest, a disease or pest can be slowed by the variety of species present. In a monoculture, once the invader adapts to its host, it can spread without resistance. If a nematode as aggressive as B. xylophilus were to take hold here, the uniformity of radiata pine plantations could turn them into a nationwide feast for the pest.

What’s at Stake

Scientists have been assessing what B. hildegardae could mean for New Zealand’s pine forests and for the economy. They have studied past research and consulted experts on this group of nematodes. There is still much we do not know. Continued monitoring and testing will be essential to understand its presence here, and more research is needed to determine whether it can cause serious disease.

So far, B. hildegardae has not shown the lethal impact of pine wilt nematode, but the potential risk remains significant. In Europe, uncontrolled outbreaks of pine wilt nematode are projected to cost 22 billion euros over 22 years, affecting more than 10% of susceptible conifer forests. For New Zealand, with its heavy reliance on radiata pine and on log exports to China, South Korea and other markets, a similar event could cause severe economic losses and long‑lasting ecological damage.

Nematode Villains Beyond Pines

Plant‑parasitic nematodes cause between eighty and one hundred billion US dollars in crop losses worldwide every year. Potatoes can lose 60 – 80 % of their yield, bananas 30 – 60%, and onions and garlic up to 80% in major outbreaks. Monocultures, whether of crops or trees, are always more vulnerable.

Why This Matters

Radiata pine is more than just a tree. It is an economic lifeline for New Zealand. Its dominance across our landscape is also its greatest weakness. The experience of South Korea’s battle with “pine AIDS” shows how quickly a nematode can turn a healthy forest into a wasteland. Protecting our forests will require constant vigilance, strong biosecurity and the ability to act swiftly when new threats appear.

Final Thought

A nematode is invisible to the naked eye, yet it can bring down a towering pine within a single season. When that pine is part of a nationwide monoculture worth billions in exports, the danger becomes far more than a scientific curiosity. The discovery of B. hildegardae by Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research and MPI is a reminder that in forestry, the smallest intruder can change the biggest story. The importance of scientific collections can never be overstated because they let us look into the past, understand the present and protect our future.