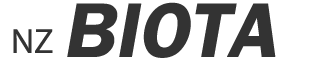

A specimen of Xanthorhoe bulbulata (Geometridae) from the NZAC. This moth is feared possibly extinct. (photo Birgit Rhode)

The discovery of the tiny black-and-white micro-moth Eudarcia richardsoni in the Swiss Alps in 2011 (Schmid 2013) was potentially devastating to the more sensitive of British naturalists.

I have heard no reports of weeping and gnashing of teeth, but national pride was surely dented, and doubtless others, like myself (an ex-pat for the last 22 years), had to sit down with a cup of tea. Previously the moth had only ever been found in southern Dorset.

In one gut-wrenching moment, the number of moth species considered endemic to the British Isles had been halved.

Here I use the term ‘endemic’ to denote species that are naturally restricted in range to a given area. Under this definition, those islands can still boast Epirrita filigrammaria, the Small Autumnal Moth, as an endemic species, but it belongs to a complex of very similar greyish looper moths, and is neither so smart nor so distinctive as the Eudarcia.

This leaves the percentage endemism of the Lepidoptera (butterfly and moth) fauna of the British Isles at approximately 0.04% (1 endemic species out of 2500), a reflection of the extreme effects of glaciation on these northern lands.

By contrast, the long-isolated New Zealand Lepidoptera fauna is 90% endemic to this country (roughly 1800 endemic species out of 2000). Many other orders of invertebrates show similarly high levels of endemism.

It is simplistic to conclude that New Zealand has 1800 times more significance and 1800 times more responsibility for conservation of the global Lepidoptera fauna than Britain, but the dramatic difference surely lends some urgency to the study of our butterflies and moths.

Are our butterflies and moths in trouble? The multiple human-induced extinctions in our vertebrate fauna are well known and intensively studied; Worthy and Holdaway (2002) give a masterful and melancholy account.

But documenting invertebrate declines and extinctions is notoriously more difficult. The subfossil record is largely restricted to hard-bodied insects such as beetles, which are usually fragmentary in these deposits and hard to identify.

The oldest insect collections from New Zealand date back to the middle of the 19th century, and dedicated taxonomic investigation of the fauna did not really begin until the 1870s and 1880s, 100 years later than in Europe. With its small population, New Zealand has never been able to muster the number of entomologists nor the intensity of study of many European countries.

Nonetheless, we can be reasonably certain that there have been major declines in some moth species. Moths that are relatively well represented in collections made between 1880 and 1930, and that must have been locally common, are now hard or seemingly impossible to find.

The most dramatic example is the small day-flying looper moth Xanthorhoe bulbulata, widespread in native grassland habitats in the South Island and southern North Island up to the 1930s. It was considered common by earlier collectors such as Alfred Philpott (1870-1930).

Since the Second World War, only two specimens of this moth have been found, both by Brian Patrick in western Otago. One was flying inside the Queenstown post office in 1979, and the other was caught in a light trap in the Kawarau Gorge in 1991 (Patrick 2000).

It has not been seen since and is feared extinct. The frustrating factor here is our complete lack of knowledge of the life history of this species. Like most Lepidoptera, it probably laid its eggs on one or few related plant species, the caterpillar’s hosts.

It seems likely that the cause of decline was the loss of a specific microhabitat, perhaps resulting in a dramatic decline of the host-plant, most likely a native herb (native Brassicaceae or Mentha cunninghamii have been suggested as possible candidates).

Invasion of its habitat by exotic weeds and grasses, browsing of native herbs by introduced mammals, land-use change: any or all could be to blame.

It looks as though it may be too late to save X. bulbulata. But this moth was clearly highly sensitive to environmental change, making it a ‘canary in the coal mine’ for other native grassland species. Some other endemic moths of these open habitats, such as Arctesthes catapyrrha, can survive in relatively modified ecosystems, such as roadsides and even golf courses, as long as turf is kept short and a range of herbaceous plants is still present (Patrick et al. 2019).

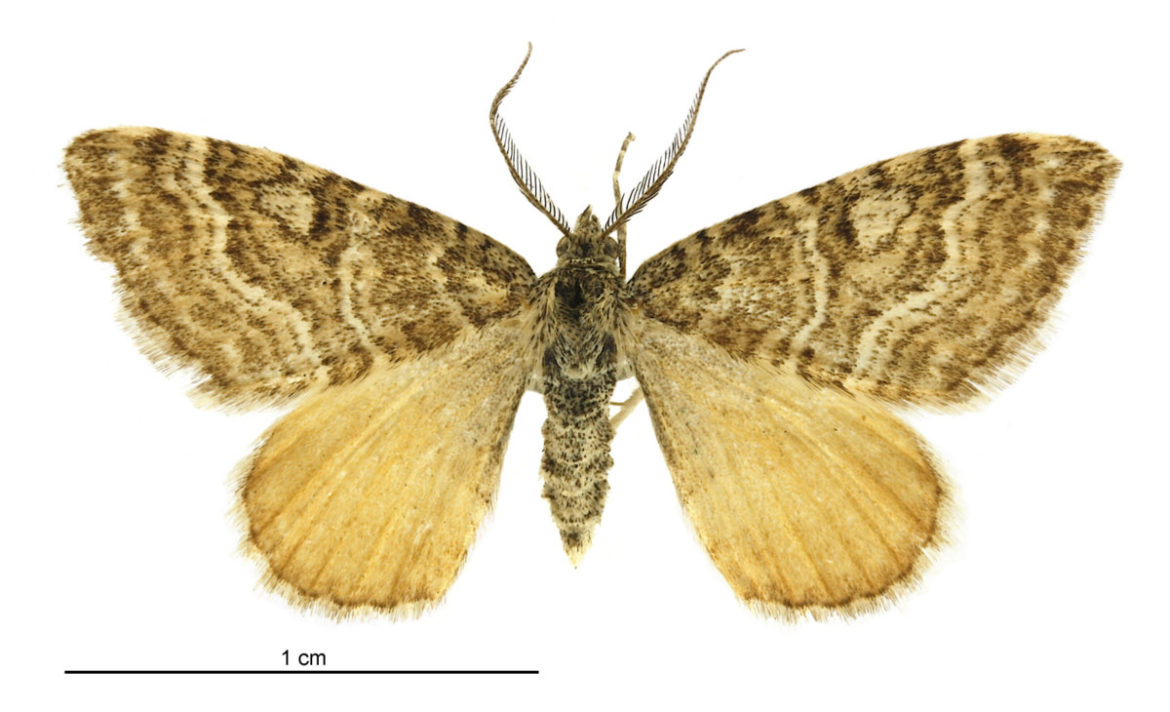

Others are now becoming ominously rare, for example the pyralid moth Sporophyla oenospora, formerly locally common in Canterbury and Otago drylands, but not seen since 2008 and feared to be on the brink of extinction. Brian Patrick and myself, supported by the Department of Conservation, are attempting to relocate populations of this species and three other short-turf specialists. Habitats have changed dramatically even in the last 15 years, and we fear for the future of these endemic moths.

These moths evolved here and New Zealand is their only home. So they are globally, not just locally threatened. Does it matter if they lapse into extinction? Already they are so rare that they are unlikely to be performing a major function in the ecosystem; they are not economically important; they may not even seem very beautiful, except to an entomologist.

Yet the same could be said, individually, for most of our endemic insects. But when we contemplate these species as parts of a much greater and impossibly complex whole, the perspective changes.

What parts of an interconnected tapestry can we afford to lose, when we cannot see the whole and don’t know which thread is connected to which?

What will we ever value if we do not value the unique and the vulnerable? It surely matters if we lose them.

References

Patrick BH 2000. Conservation status of two rare New Zealand geometrid moths. Science for Conservation 145. Department of Conservation. 21 pp.

Patrick BH, Patrick HJH, Hoare RJB 2019. Review of the endemic New Zealand genus Arctesthes Meyrick (Lepidoptera: Geometridae: Larentiinae), with descriptions of two new range-restricted species. Alpine Entomology 3: 121-136.

Schmid J 2013. Neu für die Schweiz und die Alpen: Eudarcia richardsoni (Walsingham, 1900) (Lepidoptera: Tineidae). Entomo Helvetica 6: 139-142.

Worthy TH, Holdaway RN 2002. The Lost World of the Moa. Canterbury University Press. 718 pp.