Old man’s beard looking a bit sad (photo Jerry Cooper)

Every year for the last 20 years I have gone to the annual FUNNZ fungal foray with colleagues and enthusiasts from around NZ and from overseas. Autumn is the key time of year for collecting mushrooms and the foray is the main source of specimens for my work as a mycological systematist.

This year the foray was to be on Stewart Island. I’ve never been there and so it was an exciting prospect. An exciting prospect that was dashed by COVID19. My annual foraying activity was suddenly reduced to spotting things on my daily walks with the dog around the reserve next to my house.

The joy of parks and gardens

But a mycologist can find interesting things anywhere! Over the last 20 years I have added over 100 species to the list of New Zealand fungi just from local parks and gardens in Christchurch. These are newly recognised introductions but occasionally undescribed species, and they are mostly microfungi and plant pathogens most people would not notice. Here is the tale of one new additions to the New Zealand list from my daily walk a few weeks ago during lockdown.

The reserve next door is a bit of a mess and we have just established a group of volunteers to help with weed control. Next to one stretch of path the old man’s beard (Clematis vitalba) competes successfully against the boneseed (Chrysanthemoides monilifera), and there is little else to interfere with their progress, except for the bramble, hawthorn and cotoneaster.

On this occasion I noticed the old man’s beard looked a bit sad. On closer inspection I could see many brown and dead leaves. Perhaps a fungal infection I thought? Perhaps a new bicontrol agent! I took some leaves back to my home office/lab and made some isolations. [Yes – I have a reasonably equipped lab at home with microscopes, Petri dishes, agar etc. Perhaps I’ve been unconsciously preparing for lockdown for many years 😉]

Pink and slimy

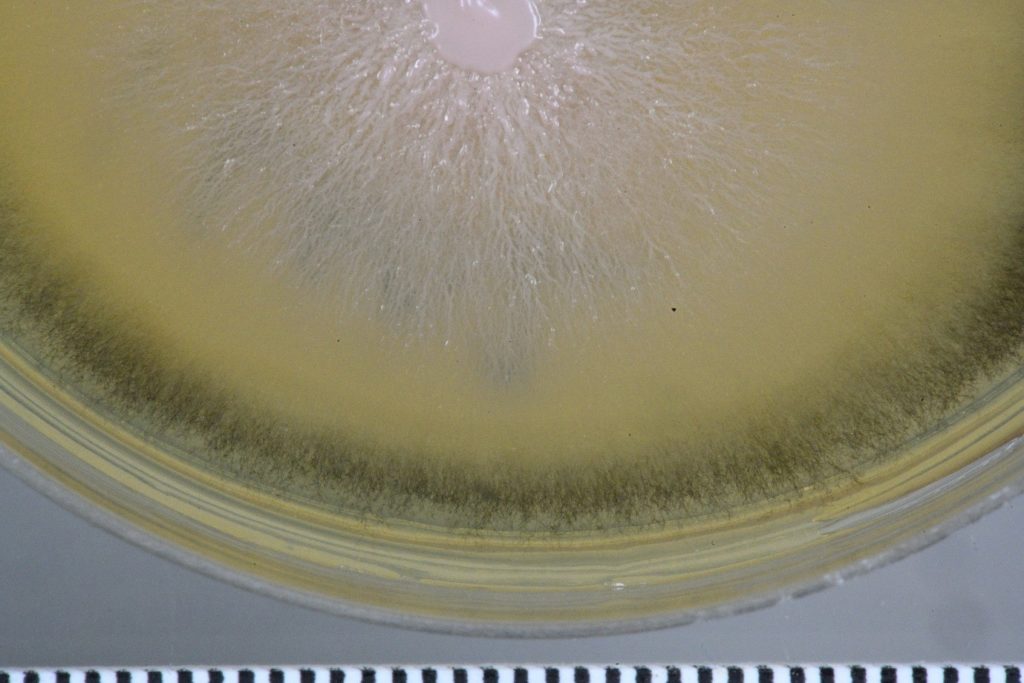

From my inoculations a rather pretty pink yeast started to grow across the plate. [Mycologists tend to have a unique sense of aesthetics]. Microscopically a yeast consists of lots of separate cells and in this case forming a slimy pink colony on the agar. After a week it transformed itself from a pink yeast into a dark green circular band of fungal hyphae around the pink centre.

Photos don’t do it justice – honestly. Hyphae are the microscopic threads associated with most fungi. I had a look through my literature for candidates with these features. [Yes – I have an extensive mycological library at home].

I had a suspicion I knew what it might be, but yeasts aren’t my area of expertise, so I needed confirmation. As usual when trying to identify obscure fungi the strongest pointers to identity come from sequence data. So, I packed my samples up and sent them to Duckchul Park, a colleague, who does the real work in sequencing them. [No – I don’t have a sequencer at home – yet]

Increasingly the identification of fungi by non-specialists relies on comparing sequence data for a specimen with entries in the global GenBank database. It’s an exercise needing considerable care because GenBank contains a lot of junk data and it is easy to be misled. There is no quality control on what gets submitted to GenBank and only the subset of data based on reliably identified material can be trusted. We are lucky in New Zealand to have authoritatively named collections held in our Nationally Significant Collections (Fungarium PDD and ICMP) backed by an increasing number of associated sequences we can use for identification.

I am always excited when I get back a new batch of sequence for specimens. Will the data confirm my identifications based on morphology? What clues do sequences provide about the things I couldn’t identify? Do I have an undescribed species? Or is this a species known to others – and did they identify it correctly? There are always surprises and puzzles to be solved.

Is it or isn’t it

In the case of my pink yeast the identity based on sequence data was clear and simultaneously both a surprise and unexpected. I thought my culture was a commonly encountered yeast-like species called Aureobasidum pullulans which I have encountered before.

However, my isolate turned out to be a closely related species not previously recorded in New Zealand called Aureobasidum subglacialis.

So, back to the literature … where has his species been found before? It was originally described in 2008 from a chunk of glacial ice submerged in seawater in Norway. It has been isolated subsequently from house dust in the USA, limestone in Portugal, marble in Namibia, as an endophyte of ash trees in Switzerland, a coalmine soil-heap in South Africa, grapes in Slovakia, and oil-treated wood in the Netherlands.

Clearly this fungus gets around a bit. A new biocontrol agent for old man’s beard? Probably not.