Root plate in the Ōparara River basin dating to the 2013 cyclone that has Mittenia plumula plants (photo David Glenny)

Goblins’ gold

On looking into the interior of the cave, the background appears quite dark, and an ill-defined twilight only appears to fall from the center on to the side walls; but on the level floor of the cave innumerable golden-green points of light sparkle and gleam, so that it might be imagined that small emeralds had been scattered over the ground.

This is how Anton Kerner von Marilaun, an Austrian botanist described the phenomenon of goblins’ gold in 1887 (translation Crum 1973).

If we reach curiously into the depth of the grotto to snatch a specimen of the shining objects, and examine the prize in our hand under a bright light, we can scarcely believe our eyes, for there is nothing else but dull lusterless earth and damp, mouldering bits of stone of yellowish-grey color! Only on looking closer will it be noticed that the soil and stones are studded and spun over with dull green dots and delicate threads, and that, moreover, there appears a delicate filigree of tiny moss-plants.

This phenomenon, that an object should only shine in dark rocky clefts, and immediately lose its brilliance when it is brought into the bright daylight, is so surprising that one can easily understand how the legends have arisen of fantastic gnomes and cave-inhabiting goblins who allow the covetous sons of earth to gaze on the gold and precious stones, but prepare a bitter disappointment for the seeker of the enchanted treasure; that, when he empties out the treasure which he hastily raked together in the cave, he sees roll out of the sacks, not glittering jewels, but only common earth.

Gold at the Ōparara River basin

Kelly Frogley and I were searching for new populations of the moss Epipterygium opararense at Ōparara River and Wangapeka Track in March this year, one week before lockdown. While searching (successfully) for this moss we often saw “goblins’ gold”.

The Ōparara River basin is an appropriate place to find goblins’ gold as Moria Gate, Galadriel Creek, Celeborn Creek, Nimrodel Creek, and Narya Creek are names from Tolkien’s “Lord of the Rings”, given to features in the basin by members of Friends of the Earth in the late 1970s when the group opposed logging of the basin’s rimu-beech forests.

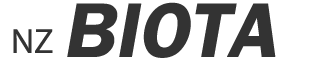

Goblins’ gold is known to Northern Hemisphere bryologists to be caused by the protonemal stage of the widespread but uncommon moss Schistostega pennata which specialises in dark cave entrances. Of the bryophytes, only mosses have a protonemal life-stage. The protonema grow from germinating spores as delicate ribbons that resemble branched filamentous algae, and the leafy adult plant later develops from the protonema once it has established.

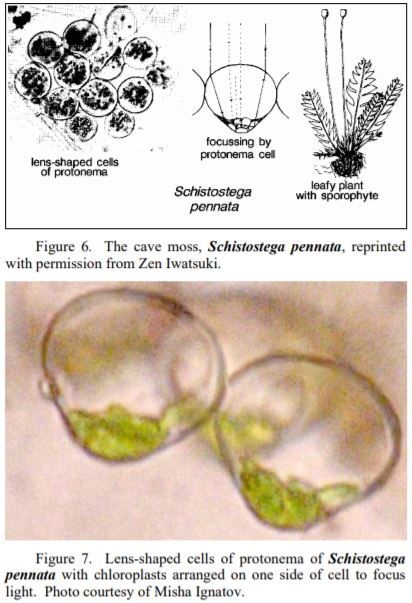

The reason for this luminescence is believed to be that the cells of the protonema are nearly spherical and act as a lens to focus light on chloroplasts at the back of each cell – see the illustrations reproduced from Janice Glime’s ebook Bryophyte Ecology.

The goblins’ gold also occurs in New Zealand and Australia but is present in the protonema of a different moss species, Mittenia plumula. This moss belongs in the same order but different family to Schistostega pennata, and the adult plant (gametophyte) has a very similar appearance of a tiny pinnate fern.

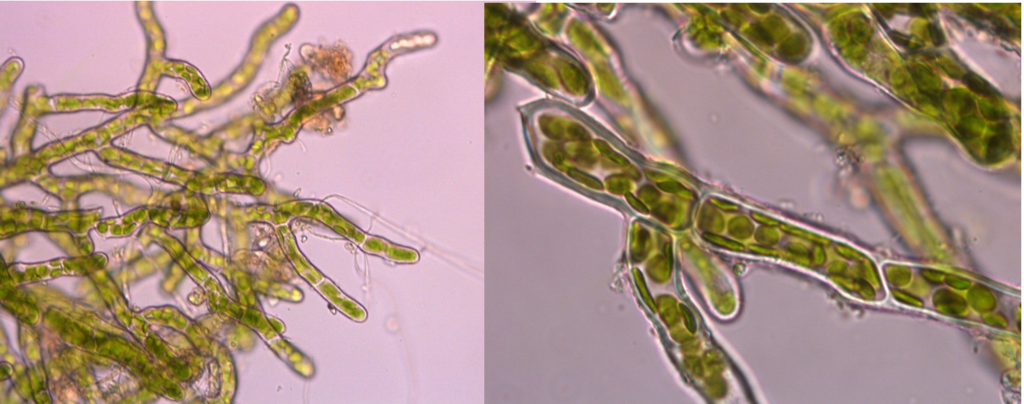

Unlike Schistostega pennata where the protonemal cells are spherical and are obviously act as a lens, the protonema of Mittenia plumula is composed of cylindrical filaments and the chloroplasts are not on one side of each cell to take advantage of focused light. Nevertheless, under the compound microscope there is a faintly visible blue luminescence from the filament walls.

Wombat holes, rabbit holes and fallen trees

In Australia, Mittenia plumula and goblins’ gold seems mainly to be found in wombats’ holes. A short YouTube video shows the phenomenon well.

Similarly in Europe, rabbit holes are habitat for goblins’ gold as shown in this YouTube video.

Goblins’ gold in New Zealand is quite common in Westland forests where trees often fall over creating a root plate that holds soil and leaves a damp depression in the ground. This is a common habitat of Mittenia plumula. This habitat is abundant at the moment after Cyclone Ita in 2013 blew down trees in large numbers in Westland forests and it is perhaps the most common moss on the tree root plates.

It is easy to photograph the goblins’ gold with a camera with an LED flash because the blue-dominant LED light is reflected back from the protonema very effectively but, appears as a luminous yellow-green glow over the soil surface.

Upon leaving the strange gems of the Ōparara Basin forests to the goblins, we found ourselves emerging into an even stranger country, one with closed borders and about to go into what we came to know as “lockdown” just one week later.

References

Crum, H 1973. Mosses of the Great Lakes Forest. Contributions of the University of Michigan Herbarium 10: 1–404.

Glime JM 2013: Bryophyte Ecology. Volume 1, Chapter 9-5: Light: Reflection and Fluorescence.